Lucky Jim: what happened when our merlin was attacked by a buzzard

/Lucky Jim

Peter Patterdale, Merlin Jim and Falconer Steve

Our little merlin, Jim, had a very lucky escape recently - he survived a buzzard attack! Here’s the story of our ‘Lucky Jim’. (Click on the images to enlarge them.)

Merlins are the smallest falcon native to the UK and, as you may already know, in birds of prey, the males are always smaller than the females. Our male merlin Jim is a tiny bird. He stands about 6 inches tall (15cm) and weighs in at only 5oz or 155g, approximately.

We got Jim in August from a top quality breeder of merlins based in N/E England. Steve has always loved merlins; he used to breed merlins about 25 years ago so he was delighted to have a wee falcon again and keen to get going with it.

“Getting going” with a new falcon means spending a great deal of time with it, in the first instance. The bird has to get used to you and its new surroundings, used to being handled and to its new ‘equipment’ - the jesses, leash and swivel.

As with all birds used in falconry in the UK, Jim was bred in captivity, so he’s not ‘wild’, as such, but he was certainly untrained. It’s Steve’s role as a falconer to train Jim, to prepare him to stand on the gloved fist, to be able to hunt, or to fly to the lure. He does this by taking him out every day, sometimes just to walk with him on the glove, other times to fly with him out in the fields surrounding our base at Hammer Inn or on site, using the lure to keep Jim’s attention here.

Jim settled in fast and was doing really well. People are often surprised that birds of prey have characters but they most certainly do and you can tell quite quickly what sort of character they have. Jim’s is easy-going; he’s very smart, gentle and keen. He and Steve clicked almost straight away and Steve was thoroughly enjoying training Jim. He even had Jim out hunting a couple of times (photos and video below), with Pete the Patterdale. (You can read more about merlin falcons and how they hunt in my blog post on Merlins.)

By early September, Jim was very much part of the team. Here he is (below) in the line-up of a static display at Wormistoune, where Steve did a falconry show to help with fundraising for Maggie’s Cancer charity. Jim was very steady on the block and his small size attracted a lot of attention, especially from children who thought his size made him a baby falcon. He is, in a way, having only been bred in May, but he is fully-grown, as all birds of prey are by the time they are 6-8 weeks old.

When not with Steve, Jim spends a lot of time on his block. He’s tethered, of course, to stop him flying away - just as you would put a lead on a dog to stop it running off - but sitting still for hours on end and just watching is what falcons do.

Birds of prey use flight as a means to escape or to hunt so one that’s fed is quite happy to sit for hours at a time, resting and not using energy unnecessarily. (It takes a lot of energy to fly!) It’s where the term ‘fed-up’ comes from: a bird that’s full (i.e. ‘fed-up’) won’t fly; it does nothing. So we say, when we’re bored and doing nothing, that we’re ‘fed up’. It’s an expression taken straight from falconry, like ‘under the thumb’!

Anyhow, one afternoon Jim was out on his block with the rest of the team and Steve had a falconry booking that he was preparing for. He had boxed the harris hawks and hooded the falcons and walked away from the weathering area to put some rubbish in the bin. Only a minute or two later he heard Jim’s kek-kek-kek cry, and knew Jim was in distress because he was shouting very loudly - an alarm call.

Steve ran back to the weathering as fast as he could.

When he came round the corner of the workshop, to his horror Steve saw a large female buzzard just taking off from beside Jim’s block, leaving Jim lifeless on the ground.

Footage from our CCTV camera

Poor Jim!

Steve went over to Jim and untied his leash and picked him up. Jim was completely still, and stayed limp in Steve’s hand. Distraught, Steve brought him into the house, convinced he was dead. However, once inside, Jim opened his eyes. He was breathing very heavily and clearly in distress so we thought he was dying and just held him in a blanket to keep him warm.

When a bird is attacked by another bird of prey, they are usually badly injured with puncture wounds from talons, or have feather and flesh torn off by the attacker’s beak. Because Jim was lying on his front, it was difficult to see any marks on him so we couldn’t tell what damage the buzzard had done.

Remarkably, within about twenty minutes, Jim started to move. We placed him inside a travel box - amazed that he could even stand - to give him a calm, quiet space to rest. But there still seemed little hope that he would recover.

A female buzzard weighs about 3lbs or 1.3 kgs and is around 21 inches (55cm) tall, so that’s quite a size advantage over little Jim!

Steve reckoned she’d only had half a minute or so on Jim before Steve had run back to the weathering but that’s more than enough time to have inflicted fatal damage. And if he was somehow, incredibly, not badly wounded, would Jim survive the shock?

Lucky Jim

Later that evening, to our surprise and relief, Jim was still alive and Steve managed to get him to eat a little. Jim had blood on his cere (the blue bit above his beak where his nostrils (known as nares) are and he was breathing heavily so still plenty to be concerned about. However, Jim spent the night in his travel box and was still going strong in the morning.

We are hugely fortunate to live near an experienced and expert falconer-vet, Keith, who practises out of the Eden Veterinary Practice at Cupar. Keith agreed to fit Jim in that morning so that he could be checked over and given antibiotics. When Steve came back with Jim later that day, we were both astounded: Keith could find no obvious signs of injury (other than the bit of blood on his cere); Jim had the laboured breathing but, otherwise, seemed fine!

You can see from the video (above) how hard the buzzard whacked Jim and you can see that she pinned him down and that Jim stops moving. It looks like she held Jim by his head with one of her talons (explaining the blood on his cere) and, perhaps, that blocked his airway so that he lost consciousness. In fact, that may well be what saved Jim’s life: it may have stopped the buzzard going in for the kill because she may have thought he was already dead.

Keith had said Jim was to be on antibiotics for 5 days and - if he made it to then - should be fine. He did and he is! He gained a little weight - up an ounce to 180 grams - which really made his feistiness come through, but that was the only change in him. Lucky Jim!

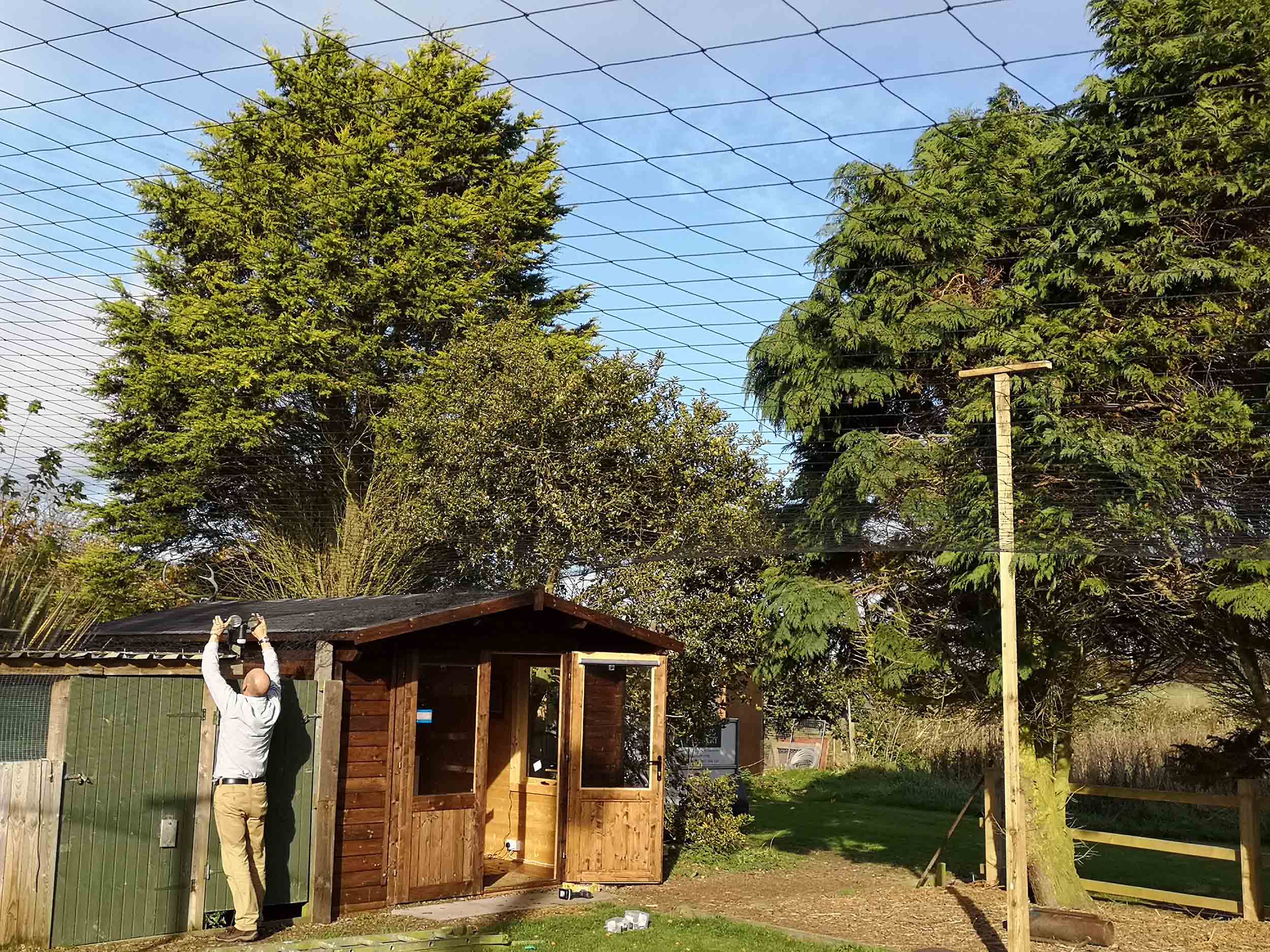

Steve’s next job was a net job. He wanted to protect the birds when they are sitting out on the weathering lawn so he ordered some 4” predator netting (used to protect ponds from herons, and the like) and installed it across the entire weathering. It’s perfect - reassuring but not too distracting.

The buzzard watched from a distant fence post while Steve put the netting up but we haven’t see her since, so hopefully she’s got the message and moved on.

Jim has now fully recovered. The hunting season has passed so it’ll be next year before Jim gets to go out hunting again with Steve and Pete. He’s back in his mews at night and frequently out on his block by day, but now safe(r) under the predator netting.

Jim’s definitely proved he’s a tough little bird and his resilience has been remarkable. He’s still in his first year, of course, and could live until he’s 12 - 15 years old, so we hope he’ll have many more years with us.

If, in time to come, you visit us for a falconry experience, I hope Jim’s still here for you to see*. And when you do, you’ll know why we might sometimes refer to our merlin as Lucky Jim.

*Or not… as it turned out. I’m sorry to say that Jim died suddenly, only a couple of weeks later, and just when he seemed to be fully recovered. We reported the news on our Facebook page.

I hope you enjoyed Jim’s story. (And if you were one of the many people who sent messages of support and good wishes to Jim on Facebook and Twitter when all this happened - thank you very much!)

Anything else you’d like to know about Jim? Or about merlins? Please ask in the comments below.

Other posts you may be interested in

Photos and video

Deborah Brazendale